Into the Dream Machine: 2020 Fiction RUNNER-UP

WORDS BY CARMEN LAC.

TRIGGER WARNINGS: death and murder, animal cruelty, medical imagery, descriptions of violence and injury, body horror.

It’s been two months since their parents have vanished beneath the weight of two cars and a semi-truck.

They’re both at the old house now, cradling mugs of milk and honey. Eloise, pragmatic as always, had been the one to broach the subject of slowly packing up the place. It feels distressingly final; even now, it seems as if the front door could swing open at any moment. As if the deceased have just been out shopping. It feels as if they could step out into the garden and see their mother among the lilies, their father reading poetry in the last rays of afternoon light.

Any moment now, only the moments always arrive hollow.

Neither of them want to let go, but it’s the logical choice. Ingrid has her own apartment near the cafe now and Eloise has lived in some other corner of the city for years. The house, stuffed with forlorn memories, would only rot in the foothills. The garden would drown in brambles.

Ingrid studies her ever-logical sister, whose eyes are red-rimmed, putting on a brave front to hide brittle feelings. Ingrid had always been the prettier twin, but Eloise had been the one who went to university and became a surgeon. Did her familiarity with bodies and death make things easier to understand and harder to endure? Was she reciting anatomy lessons in her head, the cords of tendon and muscle around bone, the tick-tock of a human heart? The science dictating why the meat and the neurons work - and how they stop? Perhaps she is reminded of their father while scalpel-deep in a broken man’s guts.

Ingrid clenches her jaw against a surge of guilt. She knows they both still grieve. But while Ingrid strolls into work to smile and sell blueberry muffins, Eloise scrubs into surgeries at three in the morning. As Ingrid counts cookies into paper bags, Eloise faces a fresh trauma at every turn.

So she offers, painful though it may be to clean away every clinging memory.

“I can take care of it.”

Eloise looks at her with tired, grateful eyes, and nods.

~

Her weekends are now for sweeping out the ghosts. She wanders the gardens, scatters birdseed over the patio, frees a panicked rabbit from a tangle of plastic waste dumped behind the garage. Her old bedroom is still intact, so she elects to sleep there on Saturday nights. She fluffs up the pillows, dusts the bookshelves, and opens her closet to see if there are any dusty bones of her youth left within.

She yelps in surprise.

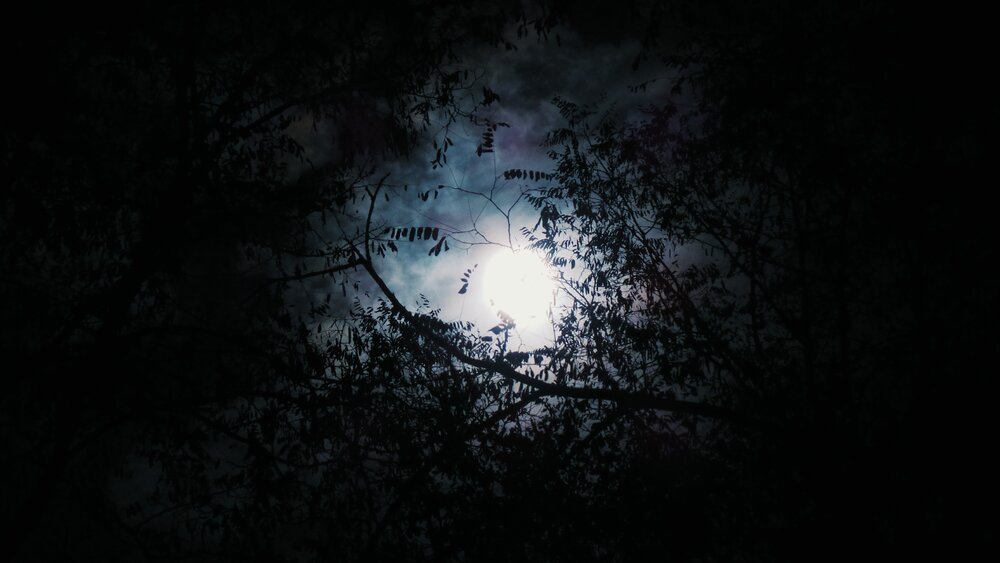

There is a dark and viscous mist behind the unassuming doors, coiling like lazy snakes and gleaming like stardust.

She stares, entranced. This is no childhood monster. Against her better judgement, she reaches out, but it’s insubstantial. Her hand goes right through, fingertips nudging past coat hangers until they brush against the smooth wooden backing. She searches for the source of the illusion and finds none. There are no projectors or lights or any explanations at all.

She stares into the void and the void ripples like a shrug, as if to say, well, what now?

Her hand hovers hesitantly over her phone. She could call Eloise. She could text a picture to her friends. She should really confirm that she isn’t going mad with grief.

Instead, she shuts the doors and goes to sleep and dreams, inexplicably, of lilies.

~

Over the following weekends, she keeps the closet doors open and takes to sorting through the never-ending tide of boxes on her bed, as if constantly glancing up at the mass of oily iridescence will help her puzzle out its meaning.

It starts with a sandwich. Shredded lettuce, halved cherry tomatoes, chopped olives, slices of ham and cheese bundled between focaccia. She props it onto a plate and balances the plate on one hand; her other hand is wrapped around a stack of books tucked against her chest and under her chin. She wobbles precariously upstairs and sets the things down too hastily, cursing under her breath when she knocks the plate over; lettuce and ham and olives roll over the floor.

The undefined thing in her wardrobe pulses and she flinches, then freezes. It surges forth with questing pseudopodia and emits a pleased sound, a faint hum just on the edge of her hearing.

When she cleans up the mess, all of the ham is gone.

The thing metamorphoses. She eats the remains of her bread and watches it change. Moving pictures flit across its surface, moonbeams and jellyfish and bioluminescence.

When she sleeps, the dreams are beautiful, and when she wakes, everything is just that little bit brighter.

~

She tries again the next week with slices of cheap deli meat. The amorphous thing swallows them down and shows her beautiful things which slide under her skin. Her head is crowned with a fluffy cloud and she is wrapped in its satiny lining. When she sleeps, she dreams of mountains scraping at the sky and underwater rivers and the yolky molten world simmering beneath the eggshell of the earth’s crust.

She starts staying over most nights so she can spend more time investigating the thing.

She tries to give it scraps of leftover cake from work - burnt offerings, old batter, sugary fondant - but they remain uneaten. Only meat seems to work.

She concludes that the thing is a carnivore.

In the morning, she sees an opossum slumped under a powerline. She pities the wasted life and takes it home to give to the thing. It murmurs happily, a scattering of lights and scenes flashing over its surface. The dreams are even more vivid that night, lattices of molecules forming a perfect geometry.

The next morning, she finds the opossum skeleton at the foot of her bed, almost intact and picked clean. Its pelt has also been regurgitated, uneaten. She is no taxidermist, so she buries them in the garden.

She treads along the highway, keen eyes picking out limp contours among the sun-bleached grass, splashes of roadkill lying along the asphalt.

More meat.

More dreams.

More bones.

~

She sees a little green lizard sunbathing on the porch tiles. Its dewy eyes blink closed and its scaly face is tilted upwards, as if in enjoyment.

It looks so fragile; her stomach lurches.

She steps forward, almost without thinking, and crushes it beneath her heel. The bones crackle as she grinds its flailing body against the stone.

She trembles after giving the lizard to the thing residing in her wardrobe, but the dreams are a soothing balm. She glides on currents beneath the ice crust of Europa and tastes starlight; a guilty conscience fades so easily.

~

There’s a tabby cat roaming around the garden.

She gives it tinned tuna, fresh water, and a place on the couch to sleep on while she watches and waits and ponders. She doesn’t give it a name.

She feels herself metamorphosing as she grapples with her evolving morality, slippery and eel-like.

The next night, she collects a fistful of lily petals. The stray is still half-starved and ever-hungry; it doesn’t need to be coaxed.

It’s not quick or bloodless. It’s horribly messy and takes several hours for the poor thing to pass and she’s choking on fear and rage and regret as she scrapes out its shallow grave with her bare hands. Teardrops dot the soil. She had been too much of a coward to get the kitchen knife or to clamber around in the garage for her father’s old shotgun and shells that she knows are still there.

Her hands are digging. They have soil packed under the fingernails. They are not bloodstained, but they might as well be.

She musters up a sick resolve and finds the gun, for next time. She can feel that there will be a next time. She knows it in her bones, fibres like roots piercing into the marrow, wrapping around her lungs and ventricles.

They feast and fester. She wonders what will inevitably bloom.

~

More meat.

More dreams.

More bones.

The lilies are growing plump and indolent.

~

She still has to work; her hours are spent thinking about the unspooling tapestry which is the thing in her wardrobe, but the refreshment it lends her after every dream is plenty enough to get her through the day.

She wonders if she is the woman called Ingrid anymore, if she is not simply skin stitched around dreams and the dark matter the thing is made of. If she were to pierce herself with a pin, would an ocean of mist and stardust pour out? Would her empty body deflate like a used balloon, layers of skin puddling onto the floor?

She’s emptying a box of plastic boxes into the dumpster out the back when she sees the little boy crying at the edge of the alleyway.

The child sniffles, wipes his face, and peeks at her between the sleeves of his jacket.

She knows she shouldn’t. Her heart pounds and every cell in her body cringes away from the very prospect. But she thinks of the weapon in her hands and the dreams in her brain, weak with greed.

She spreads a comforting smile over her face. Like buttercream icing over a decaying cake.

~

Later, she cuts bunches of lilies from the garden and puts them in a vase to mask the tang of blood lingering in the dry air.

She sits cross-legged on the floor and stares into the undulating abyss. She dreams of lush fractal worlds beyond the universe, outside all dimensions.

In the morning, the thing spits out dozens of child-sized bones.

She falls to her knees and sobs until her eyes have been wrung dry. She buries the hair and teeth and bones in the garden amongst the matted pelts of the roadkill. The clothing, she hides among the dusty boxes in the attic. She fully expects the wail of sirens outside. Lights and sounds and justice; any moment now.

But just like the hopeful moments of her mother and father pottering through the empty house, the dreaded moment never comes.

Nothing is as it should be.

~

Weeks pass.

She’s taken to going clubbing in glittery dresses and flirting with creepy guys who try to slip things into her drinks. She feigns intoxication; when they get back to her house, she shoots them twice through the chest.

One. And two. And one. And two. A drumming cadence of lead and bone. One shot to do the job and another for luck. They burst open like clay pigeons.

It’s not bloodless. But there’s a tarp on the floor and these victims mean less to her than the lizard and the cat and the child did.

‘I’m trying to do the right thing’, she tells herself. ‘I’m trying. I really am.’

She dreams of meat, marbled and glistening, and knows that it is already far too late for that.

~

She spends hours staring into the delicious and effervescent scenes in her closet. She doesn’t feel the need to sleep anymore, except to dream. At work, her hands are shaky and her greetings clipped. Reality is split between hunting people to feed the dreams and waiting for time to pass until she can dream again. The dreams are good and the nightmares even better; car husks contorted like broken ballerinas. Black ice and the skeletons of her parents turning in their graves.

She goes out at night and hunts down bad people - bad and unforgivable people, just like her - to feed to it, but they are just fodder. It is not enough. It is never enough.

She lays awake in the dark and thinks of Eloise, of the womb that enclosed them both and of the blood that ties them together still. Heartbeat by heartbeat by heartbeat.

She thinks of the undefined thing and of transcendence.

Of the two hundred and six bones in a human body, and the meat surrounding them.

~

“Hey,” she says into the receiver. “I know you're busy, but you should come over tomorrow. I found some of your stuff that you might want to keep.”

“Really? Okay. What about your old bits and pieces?”

Ingrid swallows. “I threw them away.”

~

Tonight’s dream is different.

She is not in a cloud forest or floating above a bejewelled archipelago, or in a maze of catacombs, embracing a familiar pair of grinning skulls. She is laying on her bed in her room, disappointed and confused by the normality of it all. Until she sits up and looks.

She looks her sins in the eyes.

She sees the skeletons of rabbits and kittens and foxes and raccoons and flightless baby birds. Their slender bones and enigmatic skulls are splayed over the floorboards, accompanied by their softly glowing ghosts.

A skinny tabby cat leaps onto the foot of the bed. It mews. There are lilies sprouting from its ribcage.

A gossamer shoal of fish carve through the air, trailing bubbles. Everything takes up a shocking amount of space when it’s all squashed into her room.

A deer leans against her bookcase, neck arched elegantly. Memories resurface. They float to the forefront of her mind like bloated corpses bobbing gently in still waters. She remembers dragging its dead weight home. Hacking at bruised tissue and blood soaking into the seams of her hands. The antlers are probably still on the porch.

Wingbeats fill the air as the birds burst forth in a ragged flock from the closet door. Feathery bodies fill every square inch of the room, thudding against the ceiling, pinions smacking against her face and claws gripping her shoulders, beaks pecking at her ears and elbows as she thrusts her arms out to protect her face. She thinks she remembers setting traps for them, dotted all around the property, catching them by the score until they learned to stay away. Had it really been her, with the bait and miles and miles of string in her hands? Yes. Yes, of course it had.

And then the thing itself emerges, flattening against the walls as yet more ghosts bleed from its dark and amorphous bulk.

You know what you did, the thing says. It sounds like the child. The first one.

“No,” Ingrid cries, “no, I didn’t! Youmade me do it. Iwas wounded! Iwas lost! You’rethe monster.”

Her voice sounds weak even to herself.

The thing undulates with its own sort of shivery laughter. It pulses with impossible colours.

You had a choice, it says in the child’s voice.

The price for dreams was flesh,it continues in her own.

She squeezes her eyes shut against the tide of hungry ghosts.

They are all of the things that she has killed. She doesn’t know where all of the humans are. Perhaps they simply haven’t yet emerged from beneath the crushing magnitude of it all. But she thinks she can feel a small hand gripping her own.

There are choices.

Every word, another voice. The man in the navy jumper. The woman with the long, glossy braid. The high schooler at the library.

The thing opens its mouth and keens, a pained wail formed from hundreds of bird’s tongues.

You had many choices. And you chose them all yourself. And that makes you the worst monster of them all.

The thing is lying to her, but it is the beautiful kind of lying. The sort that contains a kernel of truth, like the pearl around the speck of grit. It lies just as she does. They stand equal to equal, dreaming up lies.

She opens her mouth to defend herself with more lustrous falsehoods, and chokes. She tastes soil. It pours down her throat. There’s clay and lizards squirming in her lungs. Ghostly bites tearing her apart.

Gentle roots caress her face as they worm their way into her eye sockets.

The lilies are going to look so beautiful.

~

Ingrid wakes. Trembles beneath the covers.

There are no ghosts illuminating the room.

In the darkness, a hinge creaks.

“Forgive me,” she whispers.

This is not justice, the thing says.

The last thing she sees is a tide of oily black teeth.

~

Morning comes.

Eloise rings the doorbell several times before she searches under the flowerpots for the spare key and lets herself into the house.

“Ingrid?” she calls up the stairs, and is met with silence. “Ingrid, wake up, for goodness sake!”

There is no familiar sleepy groan forthcoming, so she clambers up to Ingrid’s room. This had been a childhood ritual, of sorts. She reaches the door. Her hand alights upon the doorknob. She freezes.

“Oh. Oh, god. Please, no.”

Eloise had been to the hospital mortuary only once, where the sanitation staff had choked that smell out of the walls with bleach and disinfectant and had only mostly succeeded.

This scent is a little like the scent that lingers in the O.R. after a surgery and certain hospital rooms, only unbearable and infinitely worse. It is one-part latex gloves slippery with blood, one-part faecal matter, two parts fetid carrion, another part indescribable.

“Ingrid,” she says weakly.

She tries the door. A small part of her hopes it is locked.

It is not.

The smell of death hits in a wave and she braces herself.

But Ingrid is not sleeping, or hiding, or melting into the bedsheets, or scattered in broken biological tessellations over the polished floorboards.

The room is empty. Sunlight streams in through the window and dust motes swirl through the air. In a vase, lilies. The closet is full of rotting meat.

But of her sister, there is nothing left at all.

ARTIST STATEMENT

‘Into The Dream Machine’ arose from me seeing the creative competition as an opportunity to write something solely for enjoyment while completely disregarding how weird it might turn out. It was a very experimental product of merging fantastical imagery with morbid themes, thereby distorting the imagery and making it sinister by association. None of it was planned or intentional—it probably helps the final product when I don’t shy away from things requiring suspension of disbelief. I also wonder: is the story scarier if you interpret it literally, with indiscriminate murder, animal-cruelty, and a dimension-breaking closet monster? Or does it pose a more substantial dread if it’s an allegory for grief, trauma, addiction, and denial? Or hey, why not both? I don’t have the answers; this is not an English analysis class, so interpret it how you will.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This article has been reuploaded and was originally published in 2020.